Diving Into Leadership to Build Push-Button Code

“Hi everyone, I’m Sarah! I’m a Research Data Scientist at the Alan Turing Institute and I’m also an operator of mybinder.org. It’s really cool seeing how many people here are interested in BinderHub!”

And it is cool. Really cool! But also a bit scary as a room full of Research Software Engineers (each of them much further on in their careers than I am) suddenly turn to me, eager for the knowledge I was surely about to impart to them.

But let’s rewind a bit.

Joining the Binder community

It’s May 2019 and I’m attending the Research Software Reactor sprint jointly hosted by Microsoft and Imperial College London. This is a three day hackathon where researchers from different areas (though all with a computing background) come together to collaboratively build cloud-based resources on Microsoft’s Azure platform.

As for me, I’m only six months into my role at the Turing, having graduated from my PhD in Astrophysics at the start of the year. Also, my role as a “Binder Operator” is barely two months old… which is why I’m starting to feel nervous about the amount of interest in the room! This also happens to be the second hackathon I’ve attended ever, so the adrenaline is high.

So, what is this “Binder” that we’re all so excited about?

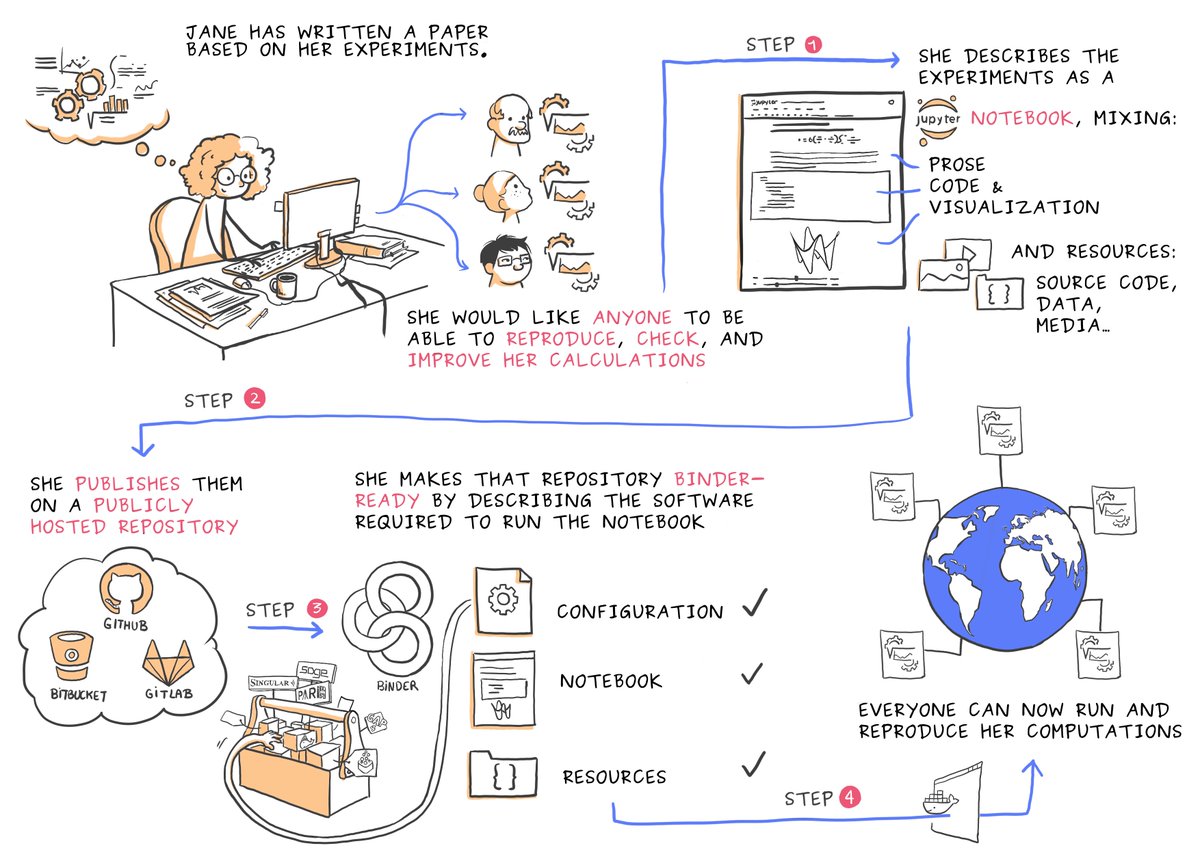

Binder is an amazing resource that can host reproducible and interactive code in a web browser. Great… what does that mean? It means that if I have some scripts or notebooks in a repository (like this one) and I describe the packages in a configuration file (such as requirements.txt), then I can go to mybinder.org, copy the URL of the repository into the form and hit launch. This will begin a series of events culminating in my notebook appearing in a browser window with all of the packages installed, and the code will just run.

Sounds like magic, right? You can even combine Binder with Jupyter Books to create interactive documents! Below is a comic explaining how a scientist may use Binder.

|

|---|

| The user experience of mybinder.org. Comic courtesy of Juliette Taka. |

BinderHub is the technology powering Binder (or where the magic happens). It is a multi-user server that can create a custom, user-specified computing environment and make it accessible via a URL. It utilises different tools to make this possible and can be deployed onto either a cloud provider or an on-premise compute cluster. These tools are depicted in the below illustration.

|

|---|

| A pictorial representation of the different tools constituting BinderHub. This image was created by Scriberia for The Turing Way community and is used under a CC-BY licence. Zenodo record. |

Since BinderHub is a cloud-neutral technology (mybinder.org itself runs on Google Cloud and OVH.com), I previously worked on refining the documentation around deploying BinderHub on Azure and ran workshops teaching people how to use Binder and deploy BinderHub. It was this work that lead to me being invited to join the Binder team. Being a maintainer for an open-source project involves checking if the service is still running smoothly and being an active, friendly member of the community - one who can answer questions when they arise.

Now that we’ve covered a bit of background, let’s get back to my slightly uncomfortable moment at the sprint.

Day 1: An unexpected leadership position

Everybody in the room is now trying to whittle down which projects we should work on - all of which are awesome! The magic of BinderHub is that it covers so many aspects of software engineering tools and practices, such as continuous integration/deployment and Kubernetes. The BinderHub idea is quickly amassing a lot of satellite projects!

“So Sarah, is it OK if I name you leader of ‘Team BinderHub’?” My second uncomfortable moment. Gerard Gorman, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Earth Sciences at Imperial and co-organiser of the sprint, has just elected me leader of my first ever hack project. If I’m honest, I’d intended to spend the sprint ironing out some niggles with a colleague. But I’ve always been a “learn by doing” person so I agree and desperately begin wracking my brain for a project to give my team for the next three days.

After a bit of shuffling (where for a while it seemed like most of the attendees would be joining ‘Team BinderHub’!), I finally assemble a team. My teammates are: Tania Allard, a Microsoft Developer Advocate; Tim Greaves and Diego Alonso Álvarez, Research Software Engineers at Imperial; and Gerard himself.

The project I decide to bring to the table is one that I’d started but had stalled. The process of deploying a BinderHub can be quite long (usually an hour) and consists mainly of typing stuff into the command line. So a couple of months prior, I’d begun designing a set of scripts that would install the relevant tools, deploy a BinderHub on Azure and connect it to a Docker Hub account, retrieve various pieces of information (IP addresses, logs, etc.) and then remove the BinderHub from the cloud. However, my bash scripting and operating system knowledge is not especially strong. Within the team, we have a bit of a discussion around the Deploy to Azure feature - a button that can be copy-pasted into the README of a GitHub project and facilitates a one-click deployment of the project to Azure. It seems like the perfect hack is to combine my scripts with the deploy button and make deploying BinderHub as easy as possible.

Tim is a bash scripting, containerising pro and has a little experience with the Azure “blue button” from the OKPy project. I ask him to check my setup script that installs the required Command Line Interfaces (CLIs) and explain that I’d like it to be generalised for different operating systems.

Gerard is a BinderHub enthusiast and is keen to get one deployed as a teaching resource at Imperial. As a starter task, I ask him to read up on how the blue button works.

Diego has never heard of Binder or BinderHub before and is quite confused as to what the rest of the team are so excited about! I suggest that he works through my Zero to BinderHub workshop in order to bring him up to speed with the concepts. This is also the perfect opportunity to get feedback on my workshop if parts are not clear! I encourage him to open an issue describing any problems he comes across or extra information he’d like to see.

And just like that, I find I’ve delegated myself out of a job!

Now Impostor Syndrome is beginning to creep up on me. Not only is it taking four extra people to pull together my work and make it usable, but I am also unsure how I would assist them in these tasks I’d set them. Especially Tim as the complexity of what I wanted the bash scripts to achieve was what had caused the project to stall in the first place.

Except there’s one very important aspect of any software project I’ve not mentioned yet: Documentation!

Since starting my position at the Turing, I’ve come to fully appreciate how fundamental good documentation is to the success of a project. Clearly written instructions covering the purpose of the project, how to install/run the code, and what kind of inputs/outputs to expect make it much easier for a new person to quickly get to grips with the project. And as result, it’s far more likely to be referenced and reused. While my team begin familiarising themselves with the infrastructure and goals of my project, I begin an overhaul of the documentation whilst keeping an eye on the repo to manage incoming issues and pull requests.

Take that, Impostor Syndrome!

Day 2: The team makes progress

It’s the second day of the sprint and ‘Team BinderHub’ gather again, our enthusiasm not diminished yet!

I very quickly set goals for the day. I want the button to work by the end of the day as I’m hoping the final day can be used to work on an idea Tania has to use Azure’s DevOps Pipelines to automatically update the deployed BinderHub as new commits come into the host repo. This would be a very handy feature for those (like me!) maintaining BinderHubs at their own institutions. Anything to automate and reduce the number of commands we have to type!

I ask Tim to begin working on the deploy script itself, to add tests where necessary and tidy up some of the parsing of the variables. The next steps are to build a Dockerfile that runs the deploy script and an ARM (Azure Resource Manager) template that controls the form the blue button links to.

Again, I’m managing the documentation, keeping up with changes we make to the code-base and functionality. Similarly, I keep watch over the repo to manage incoming pull requests and merge conflicts and also make a start on the amendments to the BinderHub workshop Diego has compiled.

My Impostor Syndrome is definitely subsiding as I begin to feel more like I understand the skills of my team and we are all making the best use of our time.

Day 3: Document, document, document

For the third and final day of the sprint we are in a new venue: the Microsoft Reactor. This is a workspace in the Shoreditch area of London where we are offered free pizza and cookies and a DJ to provide the soundtrack to our code. (OK, less an actual DJ, more of a software engineer with Spotify Premium. 😜) What I will say though, Microsoft’s beverage-making facilities have nothing on the Turing’s iPad coffee maker! 😉

Our goals for the last day? Consolidate and document! Ideally get the button working if possible, but the top priority is to make it as easy as possible for the team (or someone new!) to come along to the repo and finish what we have started.

We decide that there isn’t enough time left or infrastructure in place to implement the Azure DevOps Pipeline for automatic upgrades; instead, Tania begins working on a tutorial so we can implement it later.

Tim and I end up in a bit of GitHub hell as we realise that the code to create the Kubernetes cluster is in the setup script, not the deploy script. We refactor some parts so that all of the resources are deployed from the deploy script, and this also means that the Dockerfile only needs to find one script to execute. However, this refactoring causes a complicated merge conflict and some of the bug fixes Tim implemented disappear in a squash merge. (This sounded difficult enough to resolve that I’ve been put off learning about squash merges since!) As team leader, I try to orchestrate whose pull request should be merged first so that all the right code ends up in master.

What did we learn and do?

By the end of the sprint, we don’t quite have a working button deployment, but we do have:

- a set of streamlined scripts for auto-deployment based on the contents of a JSON file,

- an ARM template and Dockerfile that will provide the back-end to the blue button after some further debugging,

- a plan to move the project forwards after the sprint.

So what did I learn from those three days?

Coding with other people is fun!

Pair programming is something we try to achieve at the Turing, but it can be difficult to do depending on the project and the time constraints of those working on it.

This was the first time I’d experienced true collaboration. Where I had an idea that I wasn’t sure how to implement, and someone with the skills had helped me shape it and realise it. It gave me a sense of community and belonging. I hope I’ve forged connections with ‘Team BinderHub’ that will last the duration of our careers and we can work together again.

There’s a role for everyone in a team and these are equally important

Even if it’s reviewing code or writing documentation, these are as important (arguably, more so) than the code itself. Code that does what you think it’s doing and has been explained well will have a much longer lifespan than code that is difficult to follow, regardless of how clever it is, and poorly documented.

I found my strength as a leader

You might remember at the beginning of this blog post I mentioned that I’d never led a hack project before, so I also learned a lot about my leadership capabilities.

I think I did well. I identified the strengths of each of my team members and gave them a task suited to them whilst letting them explore new concepts, offering my own insight and opinions when required.

I also think that it was a good choice for me to not be too involved in the coding aspect of this project. Managing the flow into the repo and updating the documentation as new code came in meant that I managed to maintain an overall perspective of the project and could switch gears as questions came in from different areas. I don’t think I could have maintained such a view if I’d been buried in code and I can always learn from the scripts we’ve developed at a later point.

Hackathons are not where projects end

While the first 80% of a project to get the infrastructure in place can be achieved in a short amount of time like a hackathon, the last 20% is hard and often takes longer. But this extra effort is necessary for the software to be taken up by others.

‘Team BinderHub’ continued working on this project over Slack and GitHub to finally make our version 1 release on June 11th - almost 3 weeks after the end of the sprint!

If you’d like to try the button to deploy your own BinderHub (or contribute a new feature!), the repo can be found here 👉 alan-turing-institute/binderhub-deploy. Look for the button below!

Thank You! 💖

I’d like to thank a few people who made this possible:

- Gerard, Imperial College, Tania and Lee Stott from Microsoft for organising such an inspiring event;

- ‘Team BinderHub’ for coming along on this wild ride with me;

- The Binder Team for accepting me into the community and giving me the space to develop such projects;

- and The Turing Way team who introduced me to Binder and the value of community (and documentation!).

Note: this is cross-posted with The Alan Turing Institute blog and the Jupyter blog.